A few days ago, the Wall Street Journal published an unnerving article, titled Does Warren Buffett Know Something That We Don’t?.

At first glance, I’d say, well, of course! He’s a very smart guy, and he’s 94 years old. I bet he knows a lot of things that we don’t.

But on further inspection, the article had a particular theory in mind, summarized well by the following excerpts:

“When the world’s most-followed investor doesn’t feel comfortable investing, should the rest of us be worried?”

“Warren Buffett, who has quipped that his favorite holding period for a stock is “forever,” continues to have substantial money at work in American companies. But he has never taken this much off the table either—a whopping $325 billion in cash and equivalents, mostly in the form of Treasury bills.”

“Could it also mean that Buffett sees value in keeping dry powder ahead of the next crisis or general froth in the market? Yes, but he isn’t saying [that]”

I think the Journal is a great publication. That being said, it has the same “if it bleeds, it leads” bias that news has in general—its easier to get clicks when you make things sound more dramatic. And I think that’s some of what is happening here. A few points:

Saying “Berkshire has never had more cash” is kind of like saying “house prices have never been higher.” It’s a thing that, even if just mechanically due to inflation, is usually going to be true. A headline that could be written in almost any year.

That’s not to say I’m pushing back against the idea that it would be possible for Berkshire to be relatively MORE overweight cash than normal. But that claim requires we measure the amount of cash relative to some benchmark. The one that makes sense (and the one that I bet Berkshire management actually uses) would be “how much cash are the holding relative to the value of the whole company?” For instance, if the company doubled in value, they would need to double their cash holdings to be able to continue to make these strategic, opportunistic investments at the same rate. This graph shows the value of Berkshire relative to the cash and short-term investments figure quoted in the Journal article.

The blue line is the value of Berkshire. The green line is the value of their cash and short term investment holdings. The red line shows the ratio of cash holdings to the value of the business. You can see this ratio is NOT at an all time high. Its slightly lower than 2020, lower than three points in the early 2010s, lower than a large stretch of time in the early 2000s, and a point in the mid 2000s.

So, my first point of pushback would be that, to me, the increase in cash looks MORE like catching up from having a relatively LOW level of cash over the last two years than it does like an unprecedented strategic shift toward cash. In fact, looking closely at that red line, it looks like basically over the last 25 years Berkshire is almost ALWAYS holding between 20-35% of its value in cash, with a few brief spikes above that. I think that proves the opposite of what the article is implying: Berkshire is not fully invested in normal times and then strategically moving toward cash right before buying opportunities—if they COULD do that, it would be a better strategy than what they are doing. What they actually are doing is keeping a fairly steady cash reserve over time, so that whenever the next recession happens to come, they are always ready. If they could successfully time the market and only hold cash right before a downturn, it’s awfully suspicious that they choose not to.

My second point would be to hone in on what lessons we can draw from Berkshire holding this much cash. Here’s an article from back in 2008, when Buffet made one of his famous investments in the (at the time) desperate Goldman Sachs.

“On Tuesday, Mr. Buffett says, he was sitting with his feet on his desk in Omaha, drinking a Cherry Coke and munching on mixed nuts, when he got an unusually candid call from a Goldman Sachs Group Inc. investment banker. Tell us what kind of investment you’d consider making in Goldman, the banker urged him, and the firm would try to hammer out a deal.

Out in Omaha, Mr. Buffett had been fielding calls for months from Wall Street firms and other investors who wanted him to take part in rescue efforts. The first major pitch came on Saturday, March 15. Bear Stearns was reeling after clients had removed billions of dollars from the securities firm. Federal regulators were pushing for a white knight to buy Bear Stearns before the Asian markets opened late the following day.

Mr. Buffett received a call at 4:30 p.m. that Saturday from a private investment firm trying to assemble a group to buy the embattled financial giant. “I’m calling about Bear Stearns,'” the private investor began, according to Mr. Buffett. “Should I go on?'”

Mr. Buffett recalls thinking: “It’s like a woman taking off half her clothes and asking, ‘Should I continue?’ Even if you’re a 90-year-old eunuch, you let ’em finish.” Mr. Buffett says he passed on the proposed deal. Bear Stearns was bought by J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. the following day.

A few weeks later, in April, Lehman executives made a pitch to Mr. Buffett to participate in a round of financing. Mr. Buffett says he felt the Lehman offer was unrealistic and he decided not to participate.”

This same dynamic is highlighted in many of the (to me, thrilling) non-fiction books that have come out documenting the day by day and hour by hour events of the financial crisis. But the point here is, Warren Buffett has carved out a niche. If you read that full article, you’ll see the value isn’t necessarily that he has a lot of cash—its that:

- Everyone knows he’s always holding a lot of cash, such that everyone who needs a bailout has him at the top of their list in times of crisis, as a one-stop-shop for raising capital (much easier than securing a consortium of dozens or hundreds of investors)

- Because he’s known for this, he gets the first look (and best terms) at most deals in these situations

- Because he’s regarded as a wise and discerning investor, his investment in companies (especially in times of crisis) is seen as making the company more valuable.

So, translate all that on to us! If we hold a lot of cash before the next recession, is Goldman Sachs going to call us? No. If Goldman Sachs does raise equity in desperation in some public way where we would have access, are we going to get more favorable terms than other people? No. If we invest in Goldman during a crisis, is that going to be positively reported in the Wall Street journal and put other investors at ease? No.

My point is: Buffet has a really unique ability to capitalize on his consistent cash holdings that other people don’t. He does know something we don’t: among other things, the cell phone number of Goldman Sachs CEO. Does that mean there is no lesson there? Not at all! I think there is a great lesson there. Something that Buffet knows that many, but not all,people don’t know. Buffett knows his best investment strategy involves allocating capital in a way that plays to his unique strengths and competitive advantages. We should do the same.

What are our competitive advantages? Unfortunately, not close relationships with Fortune 500 company boards. And not a net worth so large that we can singlehandedly rescue troubled banks with a fraction of our wealth.

We do though have a uniquely long time horizon. The fact that you don’t need to access the majority of your liquid net worth in a short time horizon is a huge advantage over many investors. It’s both an advantage because many investors need the cash sooner than that and genuinely cannot risk the short term fluctuation of the value of their holdings, but also because many investors don’t have the mental wherewithal to stick to a long term plan. Some can’t handle the emotional reaction to short-term market gyrations, some only give into their most fearful impulses and bail on their plans during times of intense uncertainty, and some simply submit to the siren song of perpetual doomsayers, convinced the inevitable era of decline and decay is always right around the corner.

To that last point, this section of the article is worth addressing too:

“With T-bills now yielding more than the prospective return on stocks, it might seem that Buffett has taken as many chips off of the table as possible since there is no upside in risky stocks. But he is on record saying that he would love to spend it.”

I won’t belabor the point, but this by definition makes no sense as a statement. Now, it is coherent to say “I have a minority view that the market is mispricing stocks, and stocks will underperform T-bills over ___ time period”. On average, that has historically been an extreme loser of a bet. But, who knows! The market isn’t always right, and stocks do underperform T-bills over some historical time periods.

But, if the market generally believed prospective stock returns were lower than T-bills, the price of stocks would drop such that prospective stock returns rose to a level that could attract capital again. The author, in other words, is being extremely cavalier in assuming that they know “the prospective return on stocks.” If they did, they’d be making billions trading stocks; they would not be an editor working for the Wall Street Journal.

But, as a grand finale, lets examine what I think may be the most dubious statement in the article:

Giant asset manager Vanguard recently predicted an annual return range of 3% to 5% for large U.S. stocks and just 0.1% to 2.1% for growth stocks over a decade.

Here’s a link to a forum post that’s almost exactly 10 years old. I am not linking directly to the Vanguard 2014 capital market projections PDF, because it appears those links have been deactivated (try clicking on the links to them in the forum post!)

Here’s one of many similarly themed comments made on that forum at the time:

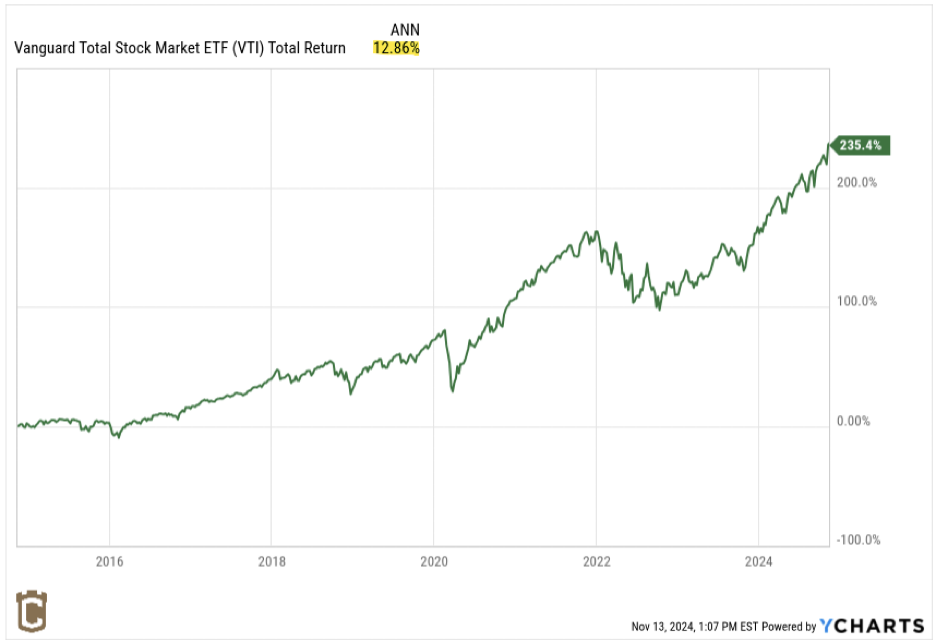

Was this poor anonymous internet soul correct that Vanguards below average equity return projections were too optimistic? What actually happened to US equities since 2014?

Oh, just an almost 13% annualized return, which was above the long run average return for US stocks over the last 100 years.

Every year, very smart people say valuations are too high and returns are destined to be lower over the next decade. Surely, if they keep saying that every year, at some point they will be right. But forecasting rain every day until it happens doesn’t make you a good meteorologist. And similarly, I don’t put much faith in these types of prognostications when the implications of them have proven to be so extremely destructive to client wealth and success over such a long period of time.

To conclude, I’ll say this: the future may hold bad things. That is always true. That always has been true. There is no guarantee that the upward march of prosperity will continue in the future.

But, I do guarantee that, if it does, there will always be (as there always has been) a loud chorus of people spreading doom and gloom along the way. And, over the last 100 years, the most important and reliable investment advice has been to tune that out!