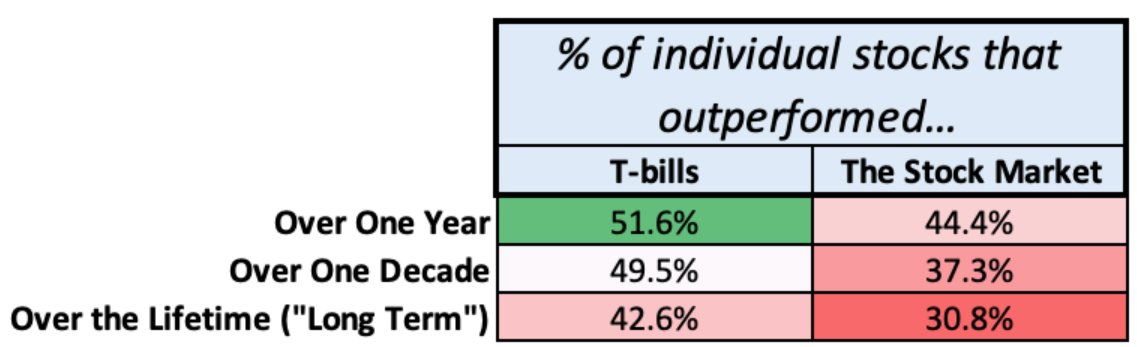

Last month, we talked about how the odds are stacked against you when trying to pick individualized stocks. But what are some of the things that dictate just how risky individual stock picking is?

How long?

On the other hand, the question of “how long do you intend to hold the stock?” has a more universal impact on a portfolio, regardless of your unique situation.

Again, your intuition may be pointing you in the right direction already: the shorter the time period you hold the stock, the less risky that holding will be.

So, all else equal, minimizing the holding period of individual stock positions can greatly reduce your risk of underperformance. Note that, this is almost the opposite conclusion about the stock market in general, where the longer your holding period, the less likely you are to lose money or underperform T-bills.1

Principle #3: Holding period matters. The less time you hold individual stock, the less risk you are exposed to. Winding down positions in a few years can eliminate much of the risk associated with holding individual stock positions long term.

Which stock?

So far, in analyzing risk, we’ve assumed an individual stock is picked at random. But is there anything we can do to analyze the risk of holding a particular stock? We are not the first to ask this question, and there have been many attempts by academics and practitioners throughout the years to answer this very question.

A simple approximation is to look at a stock’s “beta.” Beta answers the question “based on historical data, how much will this individual stock’s value change when the stock market’s value changes?”

For example, if a stock’s beta is 1.5, it would be expected to rise or fall 1.5x as much as the market. That would mean, all else equal, we would consider that stock to be riskier than the market.

However, there are many well-documented shortcomings of using Beta to estimate risk or returns on individual stocks.2

Here are the Betas for a few Oklahoma domiciled publicly traded companies, as of 4/21/2023:

- OG&E: 0.71

- BancFirst: 1.07

- Paycom: 1.41

- Devon Energy: 2.36

So, based on this simple measure, 3 of these companies have shown higher risk than the market, and one has shown lower risk. Looking at these companies, these results may seem fairly logical. The oil & gas business is famously volatile, with revenues being highly variable based on the market prices of oil & gas. On the other hand, providing electricity is a typically much less risky endeavor.

So, as a gut-check, looking at a stocks Beta to determine how risky it may be in your portfolio is a logical first step.

Looking forward

However, one of the shortcomings of Beta is that it is backward-looking. It looks at the historical change in a stock’s price relative to the market. And while that’s a decent starting point for thinking about forward-looking risk, it’s not perfect.

To get a better handle on future expectations of risk, we may be able to look at a measure called implied volatility.3

For many stocks, there is an active market for something called stock options, where investors buy and sell the right to either purchase or sell a stock in the future.

A crash course on stock options is beyond the scope of this writing, but the important point is that we can use fancy math to see, based on market prices, how volatile the future stock price is expected to be.

In fact, some companies with certain forms of compensation (like restricted stock or stock options) must disclose this estimated volatility in order to value compensation for their financial statements. Here is Paycom’s estimated volatility for their stock over the last few years:4

Paycom’s estimated volatility of around 30% is higher than the long-term average of the US stock market, which is around ~16%.5

As you can see here, we’re getting conflicting stories: Paycom’s “Beta” told us Paycom was ~1.5x as risky as the stock market, while estimated volatility shows Paycom closer to 2x as risky as the stock market.

That brings us to principle #4:

Principle #4: Measures of individual stock risk, like historical Beta or implied volatility, can help give us important context about an individual holding. But, since no one can predict the future, these measures aren’t a crystal ball, and shouldn’t form the basis of a long-term investing plan.

Again, that’s not where the principles will end, but it is where our article ends today. We’ll be continuing to outline additional principles over the next few months, so stay tuned!

Sources:

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2900447

- https://www.bauer.uh.edu/rsusmel/phd/Fama-French_JFE93.pdf

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/iv.asp

- https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net (Pg. 44)

- https://www.portfoliovisualizer.com/backtest-asset-class-allocations

The content of this article is developed from sources believed to provide accurate information. The information is not intended as tax or legal advice. Please consult legal or tax professionals for specific information regarding your individual situation. All expressions of opinion are subject to change. This content is distributed for informational purposes only, and is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products or services. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Index performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio.